Personal Assortment

Personal AssortmentAs a string of recent Banksy artworks spring up round London, an skilled reveals the clues that unlock his artwork historic genius.

Is Banksy an incredible artist? When a sequence of stencilled animals, suspended in silhouette, out of the blue started to appear throughout London in early August, one a day for every week and a half, a refrain of headlines the world over requested: what do they mean?

Warning: This text incorporates language that some could discover offensive.

Was the shock rash of work from Kew Bridge to Peckham – a spree that featured a goat, two elephants, three monkeys, a wolf, two pelicans, a cat, a tank of piranhas, a rhino, and a gorilla serving to a gang of beasts get away of London Zoo – nothing greater than a static stampede of frivolous enjoyable let unfastened within the canine days of summer time? Or does the sequence include hints of a deeper message and, simply presumably, a clue to what Banksy has been as much as all these years?

Having studied each inch of the road artist’s again catalogue for my new e book, How Banksy Saved Artwork Historical past, which explores how his work rewrites the story of artwork from prehistoric cave work to Pop Artwork, I used to be intrigued to see the place this recent path of spray paint would possibly lead us. What I discovered is that, as ever with Banksy, there may be greater than meets the attention. Take the Metropolis of London police field, the goal on Sunday 11 August of the seventh instalment on this sequence. Banksy’s intervention into the city object wasn’t almost as playful because it appeared. Removed from merely showcasing a “college of swimming fish”, as initially reported, the circling creatures fashioned a ghostly shoal of ghoulish piranhas ready to strike.

Getty Pictures

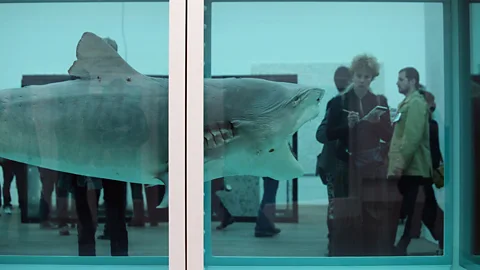

Getty PicturesBy submerging customers of the police field in a menacing tank full of ferocious fangs, Banksy not solely echoed the well-known formaldehyde-soaked shark by fellow British artist, Damien Hirst (with whom he has collaborated prior to now), however took Hirst’s work to the subsequent degree of that means. Thirty-three years since Hirst first unveiled his vicious vitrine, that once-shocking shark has begun to lose its chew. By updating the YBA icon and resharpening its resonance within the context of policing, Banksy rehabilitates a piece whose relevance was a bit of lengthy within the tooth.

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesThat is what Banksy does finest and what elevates his work above perishable pranks: he re-inflects fatigued masterpieces with a pertinence we now have ceased to consider they might have. Removed from defacing or demeaning the artists into whose works he commonly intrudes, from Leonardo to Basquiat, Banksy invitations us to look once more at what makes them nice. What follows is a range from my new e book of a few of the strongest examples of how Banksy has duffed up artwork historical past, shoved it towards a wall in the dark, and, in doing so, reinvigorated it.

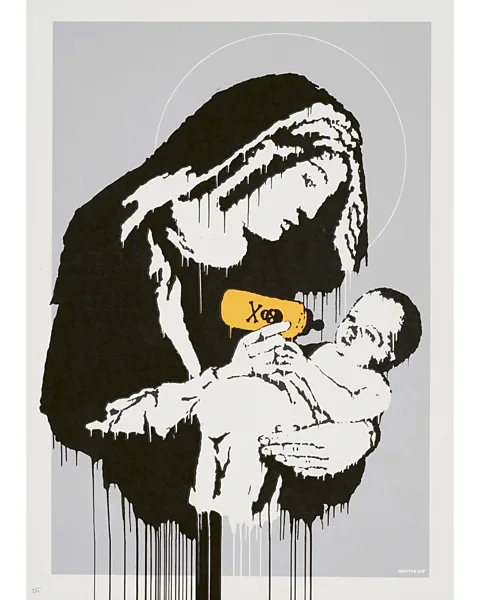

Elisabetta Sirani, Nursing Madonna, 1663 / Banksy, Poisonous Mary, 2003

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment Nationwide Gallery, Prague

Nationwide Gallery, PragueAt first look, Banksy’s disquieting 2003 print Poisonous Mary, which imagines the toddler Christ feeding from a bottle of poison, could seem merely a meme of its second. It appeared to echo the anti-religious sentiments of outstanding proponents of what got here to be often known as the New Atheism, together with Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett, who insisted that faith is a pernicious pressure. However is that basically what the picture says? Look nearer and Christ is, in spite of everything, a helpless sufferer. Recalling Outdated Grasp portrayals of the Virgin Mary nursing her son – a convention that prolonged from the late Center Age to the seventeenth Century and was recognized variously as Virgo Lactans (The Lactating Virgin) or Madonna del Latte (My Woman of Milk) – Banksy faucets right into a vein of theological thought that seeks to hint the supply of Christ’s non secular authority. The stunning picture reminds us that standard portrayals of the Mom and Youngster are something however easy or easy depictions of pure maternal love. They’re audacious maps of perilous energy.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait on the Age of 63, 1669 / Banksy, Rembrandt, 2009

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment Nationwide Gallery, London

Nationwide Gallery, LondonRembrandt noticed seeing otherwise. In 2010, a crew of researchers on the College of British Columbia proved it. Utilizing computer-rendering software program, they demonstrated how our gaze, when directed in the direction of a Rembrandt self-portrait, is subliminally lured into the Dutch grasp’s personal meticulously depicted eyes earlier than being “guided” by a sequence of cues and clues that bounce our pupils across the canvas like rigorously managed pinballs. As if anticipating the research, Banksy a yr earlier, in 2009, likewise drew consideration to Rembrandt’s eyes along with his deceptively foolish send-up of the Dutch artist’s Self-Portrait on the Age of 63 (1669), on to which he affixed a pair of joke googly eyes. By the point Banksy revealed his facetious rendition of Rembrandt’s likeness, the entire world had discovered itself sporting Google goggles when it got here to seeing, nicely, all the things. “If it is not on Google”, as the founder of Wikipedia put it, “it does not exist”. Fixated on the small screens of our smartphones, society’s seeing has altered irrevocably. If Rembrandt’s celebrated portraits are emblematic of an period that sought to see deeper and additional, Banksy’s slapstick riff affords a becoming portrait of our personal boggle-eyed, image-addled age.

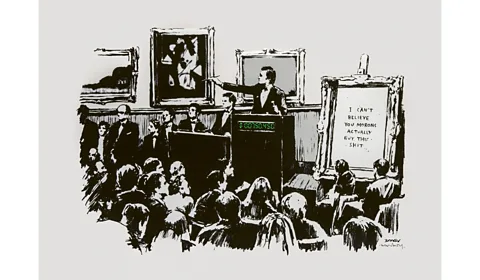

Thomas Rowlandson, James Christie on the Rostrum at Christie’s Public sale Room, 1801 / Banksy, Morons, 2007

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917

The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917There’s a lengthy custom of artists despising the very artwork world they inhabit. Take British caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson’s 1801 watercolour James Christie on the Rostrum at Christie’s Public sale Room, which questions the ethical integrity of these attending an artwork public sale. There’s something insalubriously sweaty in regards to the crush of lecherous previous males leering on the reclining nude on the public sale block as they dimension up youthful ladies within the crowded gallery. It is an orgy of ogling. Did Banksy have Rowlandson’s watercolour in thoughts when, in 2007, he created his personal unmerciful print Morons, which showcases a scrum of pretentious artwork collectors desperately bidding for a piece whose unmistakable message mocks their very existence: “I can not consider you morons truly purchase this shit”? Who is aware of. What is evident is Banksy’s unreserved disdain for an elitist scene that has witnessed his personal work elevated and feverishly fought over – despite its hasty execution and anti-establishment that means – hasn’t harmed his repute within the slightest.

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821 / Banksy, Crude Oil Jerry, 2003

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment Nationwide Gallery, London

Nationwide Gallery, LondonIn his 2003 portray Crude Oil Jerry, which summons the dappled splendour of the widely-adored English Romantic portray The Hay Wain, then units it alight, Banksy seems to disclose the “con” in Constable. The long-lasting idyll by the British panorama artist John Constable, which appears at first look to rejoice unspoilt countrysides, streams rippling with pristine water, and harmless sunshine so smooth it would not dream of damaging your pores and skin, is in fact a bunch of halcyon hooey. Even Constable, who created the work within the shuttered solitude of his studio, recalling the scene from his childhood, knew what he was depicting had already disappeared into the thickening smog of accelerating industrialisation. By superimposing – on to the pastiche pastoral of a recycled canvas – the determine of the indomitable mouse from the cartoon duo Tom and Jerry, perched upon a leafy limb, holding a can dripping with flammable gasoline in a single hand and a lit match within the different, Banksy asks us to look once more at what Constable has actually portrayed – a drained and tinder-dry deceive which we have way back put a match we won’t unstrike.

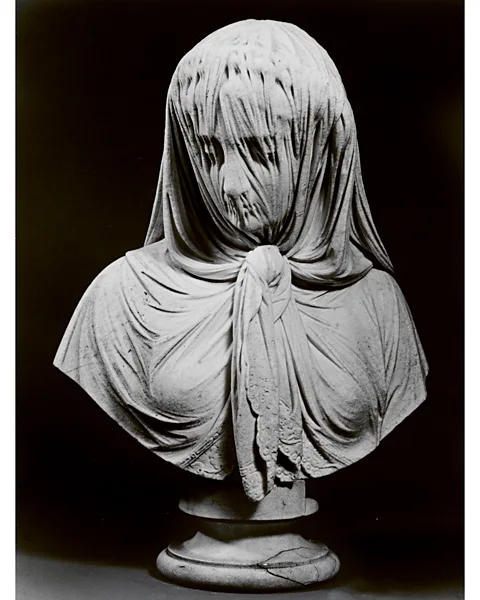

Giovani Battista Lombardi, Veiled Lady, 1869 / Banksy, Bataclan Theatre Paris, 2018

Picture Lucile Gourdon/Sipa/Shutterstock

Picture Lucile Gourdon/Sipa/Shutterstock The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York. Reward of Robert L Isaacson, 1984

The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, New York. Reward of Robert L Isaacson, 1984The bust of a veiled girl created by the Nineteenth-Century Italian sculptor Giovanni Battista Lombardi in 1869 is a miracle of poignant craftsmanship. The younger girl it portrays, frozen perpetually in mourning, is seen with a veil pulled tight throughout her sorrowful face – its fragile folds and delicate pleats preserving a semblance of her youth whereas providing a prescient glimpse of her complexion’s sluggish shrivel into previous age. The bust’s capacity to carry in equilibrium an innocence that’s slipping away and a maturity which will by no means be reached makes it a becoming supply for considered one of Banksy’s most transferring murals. Stencilled on to the exit door of Paris’s Bataclan theatre in the summertime of 2018, two-and-a-half years after that venue was the positioning of a terrorist assault wherein 90 concert-goers have been murdered by Islamic extremists, Banksy’s mural suits Lombardi’s touching portrait with a protecting swimsuit of a safety service responder. She stands solemn sentry by the door by which many within the crowd of 1,500 tried desperately to flee, haunting the portal like a soul summoned from one other world.

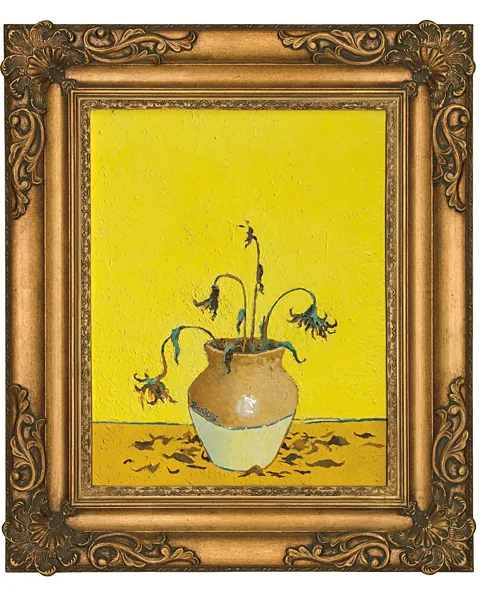

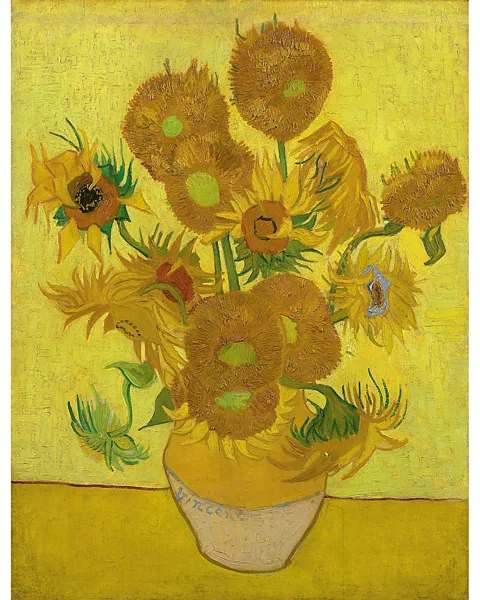

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888 / Banksy, Sunflowers from Petrol Station, 2005

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Basis

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh BasisBanksy has a knack for fracking into deep reserves of latent that means. Think about his 2005 tackle Vincent van Gogh’s revered nonetheless life Sunflowers, 1888, which the road artist rechristened Sunflowers from Petrol Station. Van Gogh’s unique canvas was begun in keen anticipation of the arrival of his buddy and fellow artist, Paul Gauguin, with whom he was planning to share a rented home in Arles, within the south of France – a go to that will flip south when Van Gogh turned a knife on his buddy earlier than utilizing a razor to slice off a portion of his personal left ear. As if seizing on the complexity of the portray’s troubled backstory, Banksy strips the bouquet’s now-stooping stems (which he has slimmed from 15 to 4), and scatters in regards to the desk on which the vase sits a ragged carpet of shrivelled florets, like so many severed lobes. By drolly dislocating Van Gogh’s intensely intimate canvas to the seemingly out-of-the-way context of “petrol stations” and “crude oil”, Banksy challenges us to contemplate to what extent that means in artwork, like fossil fuels in earth, is a finite useful resource that we are able to solely exploit for thus lengthy. Sooner or later, the vessel is empty. And so are we.

Personal Assortment

Personal Assortment Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Washington DC

Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Washington DCIn Could 2004, considered one of Claude Monet’s many depictions of a pond within the French Impressionist’s backyard in Giverny captured headlines when it sold for $17 million at auction, an eye-popping price ticket that appeared at odds with the pulsing purity of the paradise Monet was presenting. A yr later, Banksy responded, as solely Banksy might, along with his portray Present Me the Monet. Banksy’s satirical oil-on-canvas conflates three completely different instalments of Monet’s water-lily sequence and imagines the artist’s well-known Japanese footbridge embattled by the jutting fossils of city dishevelment – discarded visitors cones and the metal skeletons of stolen buying trolleys. Removed from polluting the floor of Monet’s canvas, nevertheless, Banksy’s interventions intensify points of the work which have been rusting underneath its floor for a century. The deserted visitors cones think of Monet’s uncurbed style in costly cars, which he had his chauffeur race by village streets (a behavior that earned him a visitors violation). As for the trolley, Monet was an equally incorrigible shopper. Lots of the lilies we see shimmering on the glassy floor of his work have been introduced in from Egypt and South America – an invasive observe native authorities demanded Monet cease for worry that it would place native aquatics in danger. The artist refused. Banksy’s Present Me the Monet does not deface the underlying masterpiece. It lays it naked.

How Banksy Saved Artwork Historical past by Kelly Grovier is revealed on 12 September by Thames & Hudson.